About a year ago one of the networks ran a story about a detective who found people who’d gone missing. The detective advised his colleagues to study the lost person’s photograph, then make a mental adjustment to accommodate the fact that he was over forty and had invariably lost muscle mass over the past few years. Because that was what muscles did. They disappeared. They went missing. And after you turned 60, they went missing faster.

If you’ve read much about fitness and aging, you’ve probably stumbled over this truism and maybe you’ve seen the old studies that seem to support it. But a new study by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh (published in the January edition of the journal Physician and Sportsmedicine) casts doubt on what had been considered an ironclad fact. Their study of masters athletes—people who work out 4-5 times a week—suggests that the supposedly “inevitable decline from vitality to frailty” might be more myth than we realize: “These declines may have more to do with lifestyle choices, including sedentary living and poor nutrition, than the absolute potential of musculo-skeletal aging.”

Comparing athletes from different age groups, the researchers found changes in what they delicately call body composition, meaning people got a little fatter as they aged. But “there was no decline in absolute muscle mass and the fat infiltration of muscle itself…was not increased.” And not only did old athletes retain muscle mass, they also retained muscle strength.

Granted, you can argue that maybe there is self-selection going on here: people become lifelong exercisers because they have bodies that somehow stay fit longer. Magic muscle DNA. Maybe people without some magic muscle DNA find it too hard to keep up with a five-day-a-week training regimen. Also: we’d be more convinced of the benefits of chronic exercise if the study followed these old athletes over time instead of giving us a snapshot. On the other hand, this finding isn’t a one-off. The authors identify several other studies with similar results.

So set aside your skepticism until we know better. Your choice: be the trophy or be atrophying.

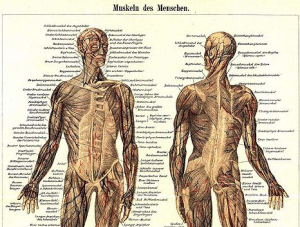

Image from Book 11 of the 4th edition of Meyers Konversationslexikon (1885–90) via Wikimedia Commons