In exercise, the flesh can be weak and the spirit too willing.

In exercise, the flesh can be weak and the spirit too willing.

You know the stories: someone your age pushed too hard and then keeled over. (In fact, this happens at all ages, but you pay more attention when the deceased is someone your age.) The more often you hear the stories, the more you think you should pay attention to your work-out heart rate, and that faint dizziness and the dull ache in your left arm that is surely a flare-up of an old ski injury or incipient arthritis or oh my god is it feeling numb I think it’s feeling numb.

Here’s another way you become obsessed with how hard you are working: your treadmill has a chart that shows age on one axis and heart rate on the other, and areas that are labeled “fat loss,” “cardio,” “athletic conditioning.” And then there’s a big area that is not labeled but clearly suggests, “Here lie dragons. And strokes.” This is the range you should probably avoid.

Then there are calories. Virtually everyone wants to lose weight, which only happens by burning more calories than you ingest. Most fitness trackers provide calorie counts based on your weight and—depending on the device—some assessment of the activity.

So two questions: how accurate are these monitors—which can be found on your treadmill, or can be purchased separately, and will probably be integrated into Apple’s iWatch if it ever appears (just a guess, but of course it will)—and what do you do with the information if it is accurate?

The short answer on accuracy, based on last year’s research by Wired and other research noted by this recent New York Times column, is…sort of.

No one questions the accuracy of heart rate monitors. Calorie measures are all over the map, though: for some activities, there seem to be consistent results among the devices. For others, the variations are stunning. An example: Wired reports that on walking tests, one device estimated a 100-calorie workout, while another tallied 450 calories, which leads to this half-hearted endorsement: “In the final analysis, these exercise monitors provide calorie numbers that are good ballpark figures, but not something you can completely rely on. To get that, you need an indirect calorimeter device, which most commonly comes in the form of a 5-pound backpack-sized contraption that analyzes your oxygen consumption using a face mask or mouthpiece.”

Oddly, a study described in the Times piece found that three trackers “accurately measured energy expenditure when the volunteers walked briskly.” (Accuracy was determined by comparing the trackers’ estimates to those of an oxygen-consumption monitor, “the gold standard in determining energy output.”) But the three devices “were far less reliable in tracking the energy costs of light-intensity activities like standing or cleaning, often misinterpreting them as physical immobility.”

On the second question—what do I do with the information—the answer is clear: not much.

On one hand, you have an accurate count of your heart rate, which some runners use to structure their work-outs, so fine. But the value of this data as a warning—am I pushing too hard?—is suspect. A fit 60-year-old can handle more beats per minute than an overweight, unfit 40-year-old. On the other hand, you have inaccurate calorie estimates, which also don’t have much value.

That said, we still want the iWatch when it comes out. And we’ll obsessively track our times and (sometimes) calories and (sometimes) the vertical feet we’ve skied and all the other obsessive stats that our loved ones find so irritating and irrelevant. Because we like to keep score, even when the tally is off.

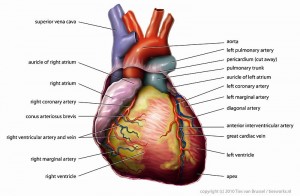

Photo: Anatomy of the human heart, in English, by Ties van Brussel, via Wikimedia Commons