Retirement planning is easy. You just need to know what food and lodging will cost over the coming decades, your age at death, your partner’s age at death, the return on the money you save, the reliability of Social Security and how sick you’ll be along the way.

Books have been written about how unknowable these critical inputs are. You must guess. And guessing wrong can mean the difference between living out the fantasy you see on evening news commercials (trim, coiffed seniors, untucked shirts over linen slacks, walking a beach at sunset) and washing the pinto pot at Taco Bell in your eighties.

There are tools to help you. To estimate your age at death, you could try this calculator from the Social Security Administration. Or, more accurately, keep trying it, year by year, because the longer you live, the longer you will keep living (actuarially speaking).

For example, if you turn 65 today you can expect to live until you’re 84. But if you keep living until you hit 70, you can expect to live another year and a half and die when you’re 85.5. You get the idea. If you were born in 1944, you’re 75 and looking at your demise in another 11.7 years (so you’ll pass away at 86.7). And if you were born in 1934, you are currently enjoying your 85th birthday: congratulations and fireworks emojis. You can look ahead to another 6.1 years before you check out. You’ll be just past your 91st birthday. (Those are the numbers for men; women tend to live a year or two longer.)

Of course, those are averages. Half of us will live longer or shorter, which means you either leave money on the table for your children (noble/stupid) or you wind up stretching your remaining money because you have zero chance of adding to the kitty.

The next unknowable is how much return you can expect on your savings. There are many confident estimates based on historical returns from the stock and bond markets. Statistically speaking, these are irrefutable…but if you look at specific time spans, the range of returns can vary considerably. And the older you get, the shorter the span you have, and therefore the greater the variability. If you are investing with a 50-year time span, you can probably get close to the historical average; if you have a 15-year span, your returns can be higher or lower.

All of which explains why it’s hard to know what to do. You can squirrel away every spare penny because you just can’t know what the future holds, or you can live a life of profligacy because if we know anything we know that life is short…or it can be short…and it would feel terrible to lie on your deathbed and realize you actually could have afforded that Jaguar, that trip to Bora Bora, that whatever makes your heart sing. (Actually, there’s no strong evidence that those are the regrets one feels approaching the white light. A good guess is that you are more concerned with your karma or your relationship with your maker or that terrible pain in your chest.)

Or maybe it’s not the ancient battle between fear and self-gratification. Maybe it’s just too hard to save anything when you have nothing, and it doesn’t help that we don’t have a clear understanding of why and how much. For whatever reason, we don’t squirrel away what we should.

A few statistics, not all of which are consistent, with sources:

- One-quarter of all Americans have no retirement savings. No surprise, almost half (42 percent) of young 18- to 29-year-olds people haven’t started saving because they have loans to pay off, houses to acquire, vacations to go on, electronics and craft beer to buy. But 17 percent of adults aged 45-59 have nada-zilch-zero set aside for their dotage. Among the non-retiree, 60 and older cohort—those who are knocking on heaven’s door—13 percent have no retirement savings. The good news is that 87 percent have something, but more than half of the group say they don’t have enough. (Federal Reserve, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018.)

- Across the Baby Boomer (born 1946 through 1964) cohort, 45 percent have no retirement savings, according to the Insured Retirement Institute, a “financial services trade association for the retirement income industry.” (Interesting detail from this report: among that 45 percent, almost one-half had savings at one time, which means they had to raid their retirement fund for living or medical expenses.) Of the 55 percent who have savings, only a third have $250,000 or more. (Insured Retirement Institute, Boomer Expectations for Retirement 2019.)

- Here’s a stunner: 35 percent of the “employees and retirees” sampled by Wells Fargo weren’t sure how much they had saved. Is there a better indication of how lousy we are at planning for the future? This is akin to driving across Nevada on U.S. Route 50—the so-called loneliest road in America—with a Post-It Note stuck over the gas gauge. (2018 Wells Fargo Retirement Study.)

- Along with the widening inequality in other parts of American society, there is a growing gap among people who have 401(k) plans. There are multiple reasons for this, but one is that the plans are voluntary. And if you are poor, you need to make a decision to invest in the future when you are struggling in the now. Guess how that shakes out. Overall savings for those 56-61 is just $163, 577, but that is misleading because it is an average. Some people have lots set aside, but almost half have nothing set aside. To get a clearer look, consider the median. Among families 56-61, median retirement savings are just $17,000 or roughly enough to buy a 3-year-old Honda minivan with decent tires. (Figures from 2013. The Economic Policy Institute, The State of American Retirement.)

Consider that you are a 50th percentile 56-61-year-old family with $17,000 set aside for retirement. Or even the average $163,577. That money, along with Social Security, will need to last you both another twenty years. It’s hard to see how that works. You’ll need more, but you don’t have it. You didn’t set aside enough because you couldn’t afford to save and even if you could there was no reasonable way to know how much to save.

Retirement planning is a deadly serious joke.

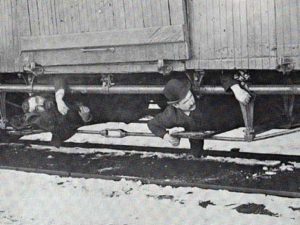

Photo: Riding the Rods, 1894, via Wikimedia Commons